|

Lesson 4

Good Roads and High Prices

|

| |

The year was 1905. A bold man drove his

new Cadillac from Fort Pierre to the Black Hills. His name was Peter

Norbeck (learn more about him in Unit 7). He was one of the first

people in South Dakota to believe in the automobile. Not everyone

was impressed. "The automobile is a plaything for idle minds

and hands," wrote one newspaper editor. It was a

"contrivance for killing people," he said.

|

|

Going across country like Norbeck did

was an adventure. Cars often broke down or got stuck in ruts or mud.

They scared the horses and livestock. They churned up dust and

splattered mud. People even wore special clothes for automobile

trips—a long coat, hat, and goggles. But cars were a new kind of

transportation. They were different from trains. People could travel

by themselves. They could go where they wanted. They were also

faster and more comfortable than horses. Soon many people were using

them. Others were building them. The Fawick Flyer was built right

here in South Dakota—in Sioux Falls. It was the first car with

four doors.

|

Photo courtesy of South Dakota State

Historical Society

|

|

Photo courtesy of South Dakota State

Historical Society

|

Roads were a problem, though. Most were

rutted wagon trails. They were unmarked, and no one took care of

them. There were no highways and no paved roads. Soon people wanted

better places to drive. Joseph W. Parmley of Ipswich started working

for better roads. He and others joined what was called the Good

Roads movement. They talked to farmers and lawmakers about the

importance of roads. They said that good roads would be good for

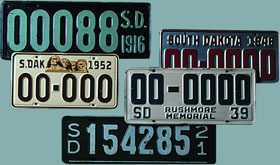

business. In 1913, South Dakota

issued its first license plates. By

then, fourteen thousand automobiles were bumping their way across

the state on unpaved trails. A few years later, the state began to

build its first highways.

|

|

|

|

|

Meanwhile, the countries of Europe had

begun the First World War. It is called this now because by the end of

it almost the whole world was fighting. The United States stayed out

of it until 1917, but then it, too, joined the fighting. Thirty-two

thousand South Dakotans fought in this war. They were from all over

the state and from all backgrounds. Dakotas, Lakotas, and Nakotas,

and European immigrants joined the armed forces.

|

Photo courtesy of South Dakota State

Historical Society

|

|

|

|

|

Photo courtesy of South Dakota State

Historical Society

|

Most of them went to Europe. Weapons had

changed since the army fought the American Indians. Bombs were now

dropped from airplanes. Tanks and submarines killed from a long way

away. Poison gases were used as weapons. People called it "The

Great War" or "The War to End All Wars." It made

Europe into a wasteland. But the warring countries still had to feed

their soldiers and their people. They bought food from the United

States.

|

|

|

|

|

Food was now in high

demand. Farmers and

ranchers got good prices for what they grew. South Dakota farmers

saw that they could make more money if they grew more food. They

borrowed money from banks to buy more land. Then the war ended.

Other countries quit buying so much food from the United States.

Prices for crops went down, and farmers and ranchers made less

money. They still had to pay taxes on the extra land they had

bought. Times became hard. Many farmers and ranchers could not repay

the banks. Many quit farming.

|

Photo courtesy of South Dakota State

Historical Society

|

Yet the war also brought

positive

changes. All American Indian men who had served during the war

became full citizens of the United States. Women earned the right to

vote in 1920 (learn more about this in Units 7 and 8). Shortly

thereafter, all Nakota, Lakota, and Dakota people also gained full citizenship. The 1920s began with hope and a new sense of freedom.

|

|

|

|

| Vocabulary |

|

| contrivance (n.),

an invention

demand (n.), the state of being wanted for use

|

issued (v.), put forth; sent out

positive (adj.), hopeful or to the good

|

|

|